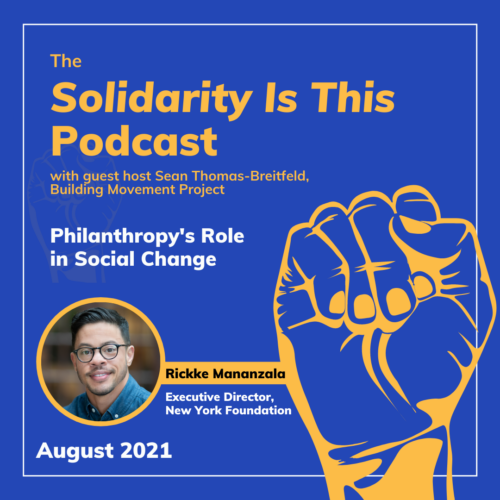

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: Hello, and welcome to the August episode of Solidarity Is This. My name is Sean Thomas-Breitfeld and I’m your guest host. I’m the co-director of the Building Movement Project. Our regular host Deepa Iyer will be back in September. In this episode, I’m in conversation with Rickke Mananzala, the new executive director of the New York Foundation. Rickke’s been a leader both from the non-profit sector and philanthropy. He’s engaged in grassroots organizing and movement building as well as social justice philanthropy. Rickke and I speak about why and how philanthropy must be responsive to the calls from leaders of color, around building sustainable movements and fostering solidarity. One of the resources we discussed in the episode is called Move the Money, a series of resources that BMP developed to encourage and invite philanthropy to support social change movements effectively. You can learn more about Move the Money at our website, www.buildingmovement.org. And now onto the podcast.

So, Ricky, let’s get started with getting to know a little bit about you and your background because you just started as the executive director of the New York Foundation and the New York Foundation, for folks who don’t know, is a racial justice funder, and a steadfast supporter of community organizing. And Rickke and I were talking before the recording started, pretty much everybody who did organizing in New York city was probably a grantee of the New York Foundation at some point. So it’s really exciting to have him in this role. Rickke, you’ve previously worked to organize donor collaboratives and supported organizing and movement building across the country. And early in your career, you were an organizer and served as the executive director of FIERCE, which is a LGBT youth of color organization here in New York city. So can you tell us a little bit about what or who inspired you to get involved in social justice work?

Rickke Mananzala: Thanks Sean. It’s so great to be here with you and reconnecting. We’ve known each other in a lot of different roles. So I think to that question more about me, my path to this work is like many people, a personal one, the who and the what are very much what drive how I stay in this work. So the first thing that comes to mind is my mom. She was an immigrant domestic worker, and I grew up watching her really struggle, both in work and managing parenting, and what it was like to be someone with limited English+ proficiency, working a low-wage jobs with little respect or dignity. So while she wouldn’t call herself an activist and I wasn’t at the time watching her go through this. And what I do remember is her coming home, frustrated, upset, and angry about what she had to endure at work

So, I think what I had developed there was just an awareness and a fire in my belly about noticing when things are wrong and speaking up about it, but not really having the outlet for that, at least as a young person, and where to go with that anger and seeing my mom didn’t have that either. And then the second thing is my own personal experience, which was when I came out as queer as a teenager, I lost the support of my parents. So I became a ward of the state and had to figure out a lot of life things on my own at a young age, which was really difficult. But it also part of that difficulty led me to a youth development services organization that helped me get some of my basic needs met and provide the support I needed to overcome some of the challenges.

And that was my path from youth development to understanding youth organizing, which was, “Oh, right. So not only can we understand that other people are going through similar life challenges for very similar reasons, and breaking that isolation and not feeling alone, but also try to understand the root causes of why we are undergoing so many challenges.” And in my case, was in schools related to racism and homophobia, and later in life, being able to connect with other people, going through similar life experiences, basically transforming individual pain into collective action. And that was so empowering to me. And I think that was my path to social justice work. That’s what landed me at FIERCE, which as you mentioned, is an LGBT youth of color organizing group in New York City that continues to focus a lot on creating safe spaces for LGBT young people, challenging criminalization, policing, and gentrification issues that many might not consider so-called “LGBT issues,” was very much a part of my organizing roots and why I stay involved in social justice work. Now, on the philanthropy side of things I know we’ll talk about, but I’d say ultimately my organizing roots are still what drive my commitment to this work. And now on the philanthropy side of things.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: Thanks. And what inspired you to make the move from organizing to being in social justice philanthropy, and also, how did your experience on the grant seeking side inform what practices you want to bring into your work as a grant maker?

Rickke Mananzala: The not so fancy answer is to say, I think it was a little bit of a mistake how I showed up to, or how I got into social justice philanthropy. And I’m still happy with where I landed, especially now being at the New York Foundation. But when I left FIERCE, I decided to go to college. I was a non-traditional student. I started organizing, I didn’t have a college degree. And so after leaving Fierce, I went to school full time and I also was working as a consultant and I was mostly focused on supporting community organizing groups and their leadership development programs, other programs and campaigns, development research and policy. But a lot of my consulting work ended up being with doing that same work, but actually for social justice foundations, both in the city and nationally.

The long story short answer to this, Sean, is that I came into philanthropy, my first job at Borealis was to help build the fund that I wish I had as a LGBT young organizer of color, eventually as a young executive director. So that fund was actually designed with not just my personal experience in mind, but talking to other young leaders and young EDS. Asking, what do you need to thrive in this role? There is a lot of pressure on you. You do not have a lot of flexible funding. You also do not have a lot of flexible funding for you specifically as a leader. And so we got to develop that first collaborative fund at Borealis and the rest is history. I went from one collaborative fund to 10 while I was there.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: So, I’m curious, what’s your view as to what the philanthropic sector has done well after the uprisings and the COVID pandemic, and what more is still needed to be done?

Rickke Mananzala: It’s a topic that stays very front and center to me as I step into this new role with the New York Foundation. I still think there is a window of opportunity to seize that momentum to continue transforming the sector. And there was a recent article I think published, you probably saw, in The Center for Effective Philanthropy by Satonya Fair from PEAK Grantmaking, where essentially in some of the data that we know thus far is that we’re seeing that there is an uneven experience of this flexibility, meaning who was actually given additional grants without being asked for a renewal proposal. What ones are given recording requirements that are either eliminated or are far fewer, what folks are getting their project grants converted to general operating. Those are all great practices that we saw, but I think the preliminary data suggestion according to Satonya is that women-led organizations, organizations led by Asian, Pacific Islander, or Middle Eastern, or other people of color communities are not receiving the same level of flexibility.

So I think we need to unpack that more and see our equity goals actually went through these simplified processes and more flexibility actually not being distributed in an equitable way. So there’s the process side of things that I think we still need to check and build momentum on to make those changes persists. And I think there is an organizing strategy to some extent around that among social justice institutions and philanthropy, but I think there is more work to be done there, but I think what is even more important right now is the commitment to racial justice and racial equity funding. Lots of statements, I think everyone has now agreed that the statements are one step. They are important. They mean something. They signal values and they signal priorities. But, when the disconnect between the statements and then the actions, understandably movement building organizations are calling out philanthropy and they want to see the money.

They want to see more than anything. The transparency around you said this, but what did you actually do? So I do think that there’s more work there and there’s still some organizing efforts and philanthropy in partnership with movement organizations to push. So, Answer the Uprising is a great example, led by the Margaret Casey Foundation and with a number of other private foundations, that are asking us to look at all of our statements around the racial justice uprisings, but specifically talking about police violence, right? A topic that, I would say, from my experience at Borealis and our collaborative funds that we started between 2016 and 2018. I can recall when we were starting the communities transforming policing fund or the Black led movement fund, there was strong interest during movement moments. And then when those movement moments faded very quickly, it was easy to measure that those dollars were gone or were significantly decreased.

Now they’re in a movement moment, we are in a movement moment again, we’re seeing a significant inflow of cash again to those funds and other racial justice funds, but will these funds persist? And so I think right now what we need is very concrete, actionable items and steps that we can take, like in Answer The Uprising: actual commitments of dollars, saying what they are, to ending police violence, then naming the commitments that we’re going to make, not just signing on, but then sharing what we’ve done or where we’ve fallen short. I think there are a few things, but I hold my breath a little bit, Sean, because I remember those ebbs and flows of funding, the ones that I’ve mentioned after Ferguson. And so my hope is that that’s not going to be the same pattern we see this year in the next few years.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: Yeah, absolutely. Let’s hope that it’s not another boom-bust cycle. And I’m curious, given your role organizing funders, particularly when you were working at Borealis, I’m curious what you learned about what it takes or what it is that funders or foundations need to learn or understand to invest in power building / movement building organizations?

Rickke Mananzala: Yeah. I mean it was constantly thought about: what are the best ways to explain the necessity of movement building and power building. When most funders are maybe interested in issues and policy change, those things are important, but where do they come from? And I found the greatest success in saying, we need the infrastructure to make these policy changes happen, but also to stick. And the only way, history has taught us, I’m not just saying that this is not only a personal opinion, but I think historically if we don’t have movement infrastructure, leaders, organizations, movements to push for these policies and systems change work, then what we land with is policies that are quickly reversed or electoral victories that are so thin that are in trouble. And so a lot of what worked across the funds and I would just say in general, across social justice philanthropy and making the case for organizing and movement building, is speaking to those funders that even if they don’t get it, we know what they care about and they care about specific measurable policy wins.

And we would just argue that those things are not possible without organizing power building and movement building led by particularly folks that have the most to lose. So when we center the margins, everyone wins. That I think is where the disconnect remains though. So folks can get that organizing and movement building is key to policy change and issue-based thinking around philanthropy. But, I think the real question is, do they have the trust in the leaders that are running that work? I know that’s a big part of what BMP does and supporting leaders of color and uplifting the work of leaders of color who are often overlooked and under-resourced in this movement building work. And so that, I think there’s more work to be done for philanthropy, to not just understand organizing and movement building as a strategy to achieve transformative change, but who is leading that work is just as important if not more.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: Yeah. Thanks so much for bringing up the leadership angle because part of what made them Move The Money project so interesting was that we were talking to both the grant makers and the grant seekers. And one of the things that really emerged from the conversations with the movement leaders themselves was they’re identifying a set of needs that they have. All of which were things that people thought funders could be investing in making possible, but weren’t seeing enough of, right. So I’m curious, given your vantage point, having been in both roles, what do you think philanthropy can do to support movement leaders, particularly leaders of color who are running very complicated organizations in the middle of a really complicated and contested political landscape where they’re constantly facing that kind of pushback? What are the things that philanthropy can do to support leaders themselves?

Rickke Mananzala: Let’s just assume all the things that we’ve maybe implied earlier in our conversation, which is the multi-year general operating support, the flexible funding to reducing the burden of the process of getting a grant. So leaders can focus on what they do best, which is not writing grants or building relationships with funders, but as leading organizing teams and power building strategies. So that just needs to be said and repeated, but more specifically, I think you’re getting into well, what does the relationship look like? What does, what are the other offerings aside from just the dollars? Although let’s just be clear that the dollars are why we have a relationship, so that they need to be plentiful and they need to be as flexible as possible. But I think some of the needs that I understand your work with Move The Money. It’s also like what are organizations going through right now that looks so different after a year and a half of living through the pandemic and racial justice uprisings.

And I think a lot of what we’re hearing at the New York Foundation. And I think as I was leaving Borealis, the start of the pandemic, what we are hearing is the trauma that people are experiencing, not just now of course, and experiencing police murders left and right even before the racial justice uprisings, but also what it’s like during a pandemic, and you don’t have that connection. You don’t have the ability to bring the team together in the same ways. And so I think what a lot of what funders can do is provide resources and their own learning on what healing justice is, how are groups thinking about supporting themselves and their teams and their communities and constituencies who have endured so much trauma? But I think the question that was always on the grantee side of things when I was an organizer, and then now on the funder side of things is this concept of capacity building is so fraught, which I’ll focus on just two things and maybe state the obvious, which is one, it takes capacity to build capacity.

So you can throw all the dollars you want at somebody to say like, “Hey, go get an organizational development consultant to do this, this and this on the strategic plan.” Great. But the groups were like, thank you for the money. We actually don’t have the capacity to even get that off the ground. So having that understanding from a funder’s perspective, even if the intentions are good, they might be signaling unintentionally a priority that the funder has, that the group does not have for themselves in regards to their own capacity. And I think the second thing and related to that, is that funders need to be thinking about grantee driven capacity building. So at Borealis, what we did was saying “Here’s $15,000, use it however you want to use it. In addition to your multi-year general operating support, decide what your capacities are and when you feel ready to take those things on.”

So these probably sound like basic things to me and you. But I know that many of our colleagues are still grappling with how to approach capacity building in a way that actually helps groups rather than overwhelms them. So that’s a few things and I think embedded in your question and I won’t carry on this topic too long because I can go down a rabbit hole of it. I think there is a lot of use of the word partner and partnership between funders and groups on the ground. And I’m evolving on this topic, but I still don’t use the word partner and that’s for very specific reasons. One, I don’t think we have an equal relationship. It doesn’t feel like we both have chosen each other on equal terms and with equal power. I’m not trying to get into our relationship metaphors here, so I’ll stop. But let’s just say like, I don’t think we’ve chosen each other. And I think we need to be mindful and be clear about what that dynamic is.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: Yeah. It’s such a great point because the word choice is aspirational probably in terms of partner, but it also hides the fact that there are these power imbalances and it becomes a way to not own the fact that in this relationship one side does have more power. And I do want to invite you to go down the rabbit hole of just talking a little bit more about New York Foundation because the foundation does have a capacity building program. Can you just talk a little bit more about how it works?

Rickke Mananzala: So our capacity building is structured, not just on our own, but what I appreciate about the foundation is that it is trying to work with other New York City social justice foundations. We have many overlapping grantees. And so what we hope to do at the foundation is coordinate with other like-minded funders as a part of the New York City capacity building collaborative. So not only are we pulling resources and offering shared workshops and other technical assistance to our grantees, but that helps get at one of the issues that I talked about, which is if you have many of the same funders and they’re all independently telling you, “Hey, we have these resources to do all these great capacity building things.” I remember as a grantee, it was so overwhelming. So to have one place where many of my funders are coordinating with each other, their capacity building efforts, is a huge help.

And that ranges from the standard things you would think around financial management team and just management in general, organizational development, strategic planning, those typical offerings. If groups want to take advantage of them they’re not imposed, but then there’s also what we do as a New York Foundation. And that’s through our summer internship and community organizing programming and providing resources for groups to support new organizers in their work. And then there’s some new things we’re learning while trying not to over survey grantees, like try to strike that balance between, “Hey, what do you need right now?” Because again, they’re getting that same survey from every single foundation. Again, the attention is good, but I don’t think we realize how many groups are getting the same survey. So using the collaborative as a way to assess what groups need.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: So Rickke, as you know, the theme of the podcast is solidarity and wanting to hear what solidarity means to you and what difference it’s made in the movement spaces that you’ve been a part of.

Rickke Mananzala: I think solidarity is resisting and the gravitational pull of zero-sum game thinking, like, so for one person to win someone else’s got to lose. And the best way I can think about solidarity for me, specifically multiracial solidarity organizing, it was my experience as an organizer in New York City. I think the primary way in which I really grew up in New York City organizing was the coalition work and multiracial coalition work. I’m thinking after 9/11. So there was racial justice 9/11 coalition, the coalition against police brutality, what then became people’s justice that then you might argue now is the next iteration and communities United for police reform. I had never experienced in organizing that level of multiracial solidarity. So if we were working on a police violence issue, there were still AAPI folks who were maybe not as impacted like Black and Latinx communities in the city around police violence, but still were visiblizing the police violence in that AAPI community space and talking about those differences, but coming together ultimately that even if one community would not bearing the brunt of police violence.

And in this case, seeing AAPI leaders stepping up and voicing solidarity with Black and Brown communities around police violence, which really very much shaped my experience of what solidarity looks like in practice. And that I think was one of the most powerful entry points into organizing in New York City. Just really, really strong, multiracial solidarity efforts. And it reminds me too, is how I’ve thought about myself, both as an organizer and now in philanthropy and de-siloing our work, because philanthropy, as we talked about earlier, if it’s set up an issue based silos or cares more specifically about policy change outcomes, we lose that potential to understand the importance of multiracial solidarity and coalition work. As an organizer I always thought about when I was at FIERCE, we saw our roles, as an LGBT youth of color organization, where do we belong?

Racial justice movement, LGBT rights movement? We could argue that in both of those spaces, we didn’t feel like we belonged in some ways. So we always were really explicit, like as young, queer and trans people of color, we were showing up in racial justice spaces and uplifting queer and trans liberation and feminist values. And in the LGBT spaces, we were lifting up racial justice and feminist values, things that maybe we saw as gaps. And we often played that bridging role across movements. And so I think when I think about solidarity, I think about not just multiracial solidarity and the importance of coalition work, but I also think about the roles that specific leaders play in building multiracial solidarity and solidarity across movements, or making them more interconnected. I may be biased, Sean, but I do think it’s oftentimes the people playing that bridging role across movements and building solidarity are LGBT people of color.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: I’m curious from the time where you’re recalling of the multi-racial coalition in New York, what did funders do? How did funders invest in those multi-racial coalitions and do it in a way that was positive and supporting coalition collaboration and not like competition, which I think too often happens otherwise.

Rickke Mananzala: Yeah. I could speak more now to how I see funding happening for coalition work, but I would say, and maybe my memory is lapsing on purpose, but if I remember that those coalition efforts, I don’t remember us getting much funding for that work, or even if it was available that we intentionally didn’t seek it, that we all pitched in our own resources. And that this was just a part of our organizing that we were going to do no matter what if we had funding. And you got to keep in mind, this was organizing a coalition specifically around police violence. That work was significantly overhauled, and that’s a polite word to say why we didn’t get funding during that time. And I’m still happy to see more funding going to work to end police violence. And there’s still a long way to go and really embracing and talking explicitly like we are talking about police violence.

We are not saying racial justice. Yes, this is a racial justice issue, but no the funding specifically to end police violence still wins. Despite what we are now, we understand now as the second pandemic and that we’ve been dealing with. And so what I see now though, with funding around coalition work, I think I would say from a funder and grantee side of things, groups are still hesitant to accept it because of the dynamics that funding often can play and being disruptive to movements and coalition relationships. So for instance, when a funder says to maybe the largest organization in the coalition, “Hey, we want to fund the coalition, but we want to give it to you in particular.” That creates the dynamics among coalition partners that is disruptive. And so I think as for the funders listening to this, I think even if a group says, “Yeah, that will work.” Everyone in the background is like, “Hmm, this could be one of the things that actually holds us back from our real potential.” So I would say trying to find other ways and funding vehicles to support coalition work and solidarity work that doesn’t create unnecessary dynamics that disrupt the work.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: Yeah. So interesting because I think that the re-granting or trickle down of funding is probably just easier for funders. I don’t know that it works better for the local power building organization that is showing up to the coalition table and actually doing the majority of the turnout. Or actually doing the majority of the on-the-ground organizing and power building.

Rickke Mananzala: I think that’s exactly it. I mean, I’m going to hone in on the one thing you said, like is a funder or giving it to the lead or the largest organization out of ease and less paperwork for them. Or could they just fund 10 organizations directly, no matter what their budget sizes are. As a way to say, “Oh, is this unintentionally creating a disruptive dynamic? Well, what’s another way that might be more work for us, but by the way, they’re doing more work than us on the ground. So, doing 10 grand agreement letters instead of one, maybe it isn’t that big of a deal when we think about the consequences of doing it another way.”

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: Thanks so much, Rickke. And so it just want to close us out by inviting you to make a call of action to our listeners.

Rickke Mananzala: Well, I think your listeners might be a mix of both movement building organizations and people in philanthropy and social justice philanthropy in particular. I think right now in this inflection point of philanthropy, my hope remains that and really examining itself as well as the movement moment that might be hitting the more quieter phase with that we still have this window of opportunity to transform the relationship between philanthropic practices, in service of movement building and power building. And my hope is, especially when I think back to the history of how FIERCE, when it was founded in 2000, it came out of the height of the late nineties and police brutality movement. So many organizations during that movement moment were started a year later. So that was Fierce, Desi’s Rising Up Moving (DRUM). And so many more that I could name. But, in these movement moments, funders need to be looking for the startups that look scrappy and what some funders might define as risky.

But remember who these organizations are today, there are so many and beyond New York City, you remember that movement moments spawn these new and exciting groups. And so funders need to be looking for them and redefining risk. And another way is saying it’d be risky to not fund them, knowing what we know now, when groups start at a movement moment. So the best way to support them is to listen, find them, talk to their partners and fund them flexibly for a long-term, even if they’re startups, and trust in their work. And I think for the groups on the ground, especially now, we’re in this moment where we’re having mega individual donors, like Mackenzie Scott who are coming in and really disrupting institutional philanthropy as practices in some ways where a group might actually turn down money from a foundation, because they’re like, “I just got a larger sum of money embedded with way more trust with fewer hoops to jump through, why would I want a relationship with this foundation?

Even if they want one with me?” No, not everyone is getting those large dollars from individual donors, but not being afraid to talk to their institutions that they’re pursuing about how they can support their work and better in different ways. But that’s going to require a shift in the power relationship. So I put it back on us and those of us in philanthropy, that if we want to have true partnership and want to truly receive that direct feedback, then have a real relationship with movement groups. We have to transform ourselves first and make that possible.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: Thank you so much again, Rickke, for your thoughts and insights and just for joining the conversation today, really great to connect with you and congratulations again on the new role. Congratulations to you and congratulations to the New York Foundation. Really excited to see what’s going to come out of your leadership there.

Rickke Mananzala: Thanks so much, Sean. I will say it is pretty incredible. It feels so full circle to remembering what it was like to be being a grantee of the New York Foundation to now helping to lead it. And I can’t imagine a better place to be carrying on my social justice work. So great to connect with you.

Sean Thomas-Breitfeld: I want to thank Rickke again for joining us on Solidarity Is This, a few weeks into his new job at the New York Foundation. We appreciate all of you who are listening and subscribing to the podcast. For more information and resources, you can check out the notes page on iTunes or our website for a transcript of this episode and links to Move The Money. You can find all of that at www.buildingmovement.org. Please come back in September when Deepa Iyer will be hosting an episode related to the 20th anniversary of September 11th. Take care and thank you for listening.