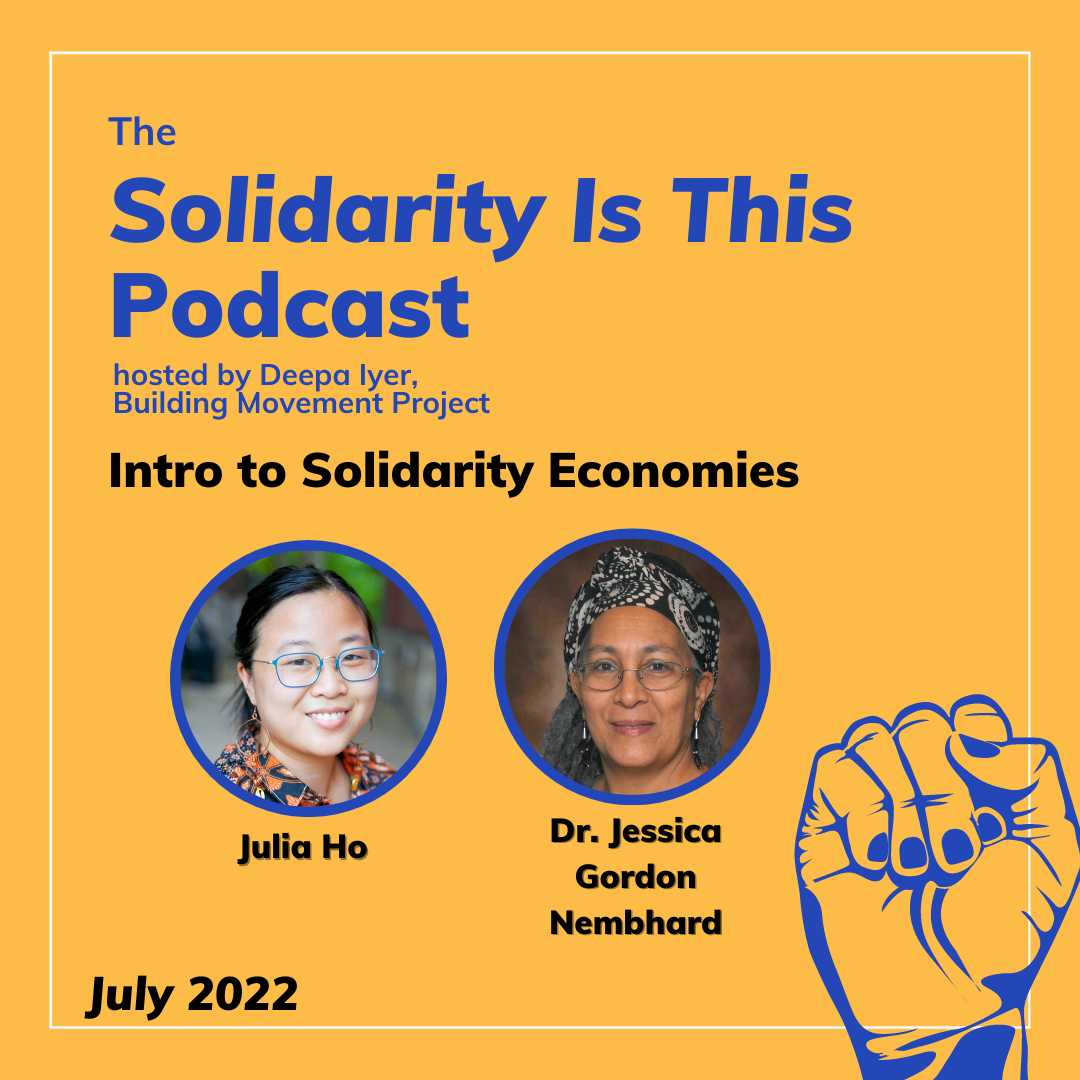

Intro to Solidarity Economies

In this episode of Solidarity Is This, host Deepa Iyer is in conversation with Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard and Julia Ho on solidarity economies, a global movement to build a just and sustainable economy that prioritizes people and the planet over profit and growth.

ABOUT OUR GUESTS

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard is a political economist specializing in cooperative economics, community economic development and community-based asset building, racial wealth inequality, solidarity economics, Black Political Economy, and community-based approaches to justice. She is Professor of Community Justice and Social Economic Development in the Department of Africana Studies at John Jay College, City University of NY; a co-founder of the US Solidarity Economy Network; and author of Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice. Jessica is also a mother and grandmother.

Julia Ho is a solidarity economy organizer based in St. Louis with deep roots in Taiwan. Julia has been living and organizing in St. Louis since 2011 and has been heavily involved in dozens of campaigns, coalitions, and organizations in the region throughout that time. She is the founder of Solidarity Economy St. Louis, co-founder of STL Mutual Aid, and board co-chair of the New Economy Coalition.

“Solidarity economics helps us to get back to our humanness, get back to those human relationships, [to] stop exploiting other people, stop exploiting the Earth."

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard

Deepa Iyer:

Hello, everyone. This is Deepa Iyer, and you're listening to the Solidarity is This Podcast. Welcome. It's July 2022, and there is a lot happening in the United States and around the world right now, from political turmoil in various nations, to the ongoing war in the Ukraine, to the deprival of basic rights from women and pregnant people under the law here at home. I hope that amidst all of this, each of you is able to find a community of people, an ecosystem, to co-conspire with, collaborate with, and to build care with because right now, deepening the ties that bind us together might be one way, the only way, to prepare for what's ahead. And that's really what we're talking about on this month's podcast.

Deepa Iyer:

We're taking a deep dive into solidarity economies. According to The New Economy Coalition, solidarity economies are part of a global movement to build a just and sustainable economy that prioritizes people and the planet over profit and growth. When we participate in solidarity economies, people get their needs met without harming or exploiting others or our planet. Solidarity economies are bound together by core values such as participation, cooperation, community ownership, respect for the Earth, and reciprocity. As you'll find out in this podcast, solidarity economies aren't new. Our ancestors practiced mutuality, cooperation, and connection in a myriad of ways, and so do we today, from mutual aid, to land trust, to barter, to crowd funding, to housing cooperatives, solidarity economies are ways for people to take care of each other.

Deepa Iyer:

So as you listen to the podcast, think about how you might already be engaging in solidarity economies. What motivates you to do so? And how could solidarity economies help us move through and past the crises we're facing today? Joining me are two visionaries and solidarity economy practitioners, Julia Ho and Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard. Let me tell you a little bit about both of them. Julie Ho is a solidarity economy organizer based on St. Louis with deep roots in Taiwan. Julia's been living and organizing in St. Louis since 2011 and has been deeply involved in dozens of campaigns, coalitions, and organizations in the region. She's the founder of Solidarity Economy St. Louis, co-founder of St. Louis Mutual Aid, and board co-chair of The New Economy Coalition.

Deepa Iyer:

Also joining us is Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard. She's a political economist specializing in cooperative economics, community economic development, and community based asset building, racial wealth inequality, solidarity economies, Black political economy, and community based approaches to justice. She's a professor of community justice and social economic development in the Department of Africana Studies at John Jay College, The City University of New York, and a co-founder of The US Solidarity Economy Network, and the author of Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice, which we'll be discussing today. Jessica and Julia, welcome to the Solidarity is This Podcast.

Julia Ho:

Hi, all.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

Hi. It's a pleasure to be here. Thanks for having us.

Deepa Iyer:

So we want to start off by actually describing what a solidarity economy is. And so Julia, I want to start with you. In your words, how would you describe the characteristics of solidarity economies.

Julia Ho:

So I can actually pull a little bit from the vision for The New Economy Coalition, which I have been a member of for about eight years, and I'm on the board of since 2016. But one of the visions that we've developed is for what it would look like to create a solidarity economy ecosystem. Some of the characteristics I think that are really key to lift up, and again, all these can be found on the New Economy Coalition website, but they're rooted in history and culture. There's a culture of reparations and restoration that we're stewarding and taking care of Mother Earth.

Julia Ho:

There's responsive participatory governments, meaning that we are making decisions together, people have agency and the ability to determine what their communities should look like. Frontline leadership, the people who are affected by oppression or any other issues and our society are the ones who are best equipped to solve it. And the last one is an adaptable to crisis, and of course, so the purpose, one of the purposes of a solidarity economy is to provide a space for people to survive through these crises, but also the rebuild the way that we want society to look.

Deepa Iyer:

And we'll also link to that vision and the web link that you offered. Jessica, what would you add to that? And also, maybe you could also give us some examples of solidarity economies that you see right now.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

So to build on what Julia already mentioned, the notion is that we're talking about values based economic and human exchanges, so we're turning our notion of the economy to humanity and to human agency, human control, mutual aid, concern for each other, care and community. So those kinds of values, self-help, care and community, caring for each other, mutuality, equity. I'm a political economist. I talk about how solidarity economics was really our first economic system and our longest lasting economic system. The system of capitalism that we're in right now, and I know we'll talk about that in a minute, is very new on a human scale. Right?

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

And if it's alienated us from our solidarity cooperative natures, and so solidarity economics helps us to get back to our humanness, get back to those human relationships, stop exploiting other people, stop exploiting the Earth. We talk about solidary economies, so that we're not just talking about nonprofits, and we're not focusing on existing hierarchical kinds of relationships. We're really talking about these human, organic relationships. They spout out from the grassroots. They're very much connected to what we do as human beings in the grassroots, not top down. Solidarity can be something as simple as barter, and that's why we say we all do this. I mean, I babysit for you, and you pick up groceries for me. You carpool this week and I carpool next week. That's part of being a solidarity economy. Fair trade is also. Right? Working with groups so that we're not exploiting the people that we're buying from, and being part of a fair trade movement, and connecting better with solidarity.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

We also talk about gifting as being in the solidarity economy. And then we talk about the more formal aspects of it, which are cooperative ownership, worker co-ops, credit unions, and where the governance structures are relatively non hierarchical as much as possible, and are about democratic participation.

Deepa Iyer:

Julia, I know you have been part of various solidarity economies in St. Louis, including one around mutual aid, as an example, that is part of I think that trajectory that Jessica described, barter, gifting, cooperative, so on and so forth. Can you describe a little bit about the solidarity economies that you are involved with in St. Louis?

Julia Ho:

I've been in St. Louis for about 11 years. I didn't grow up here, but St. Louis is home for me. And a lot of my kind of politicization can from the Ferguson uprising for Mike Brown's murder in 2014, and so much, so many people, thousands of people's lives have been really affected by that. And one of the beautiful things that started happening a few years after the Ferguson uprising was that people were really taking something that started as a movement around police brutality and state violence and really expanding it in all these different beautiful ways, and thinking about: Okay, how do we have control over our communities? And really evolving that conversation into a solidarity economy. But how are we creating a place for all of these people to have relationship with each other, and also to collaborate together in a new and different way, and to uplift all of these values and all of these things that we're talking about on a local level?

Julia Ho:

And so that's essentially what Solidarity Economy St. Louis has been doing. But where mutual aid fits into that for me is we really responded of course in response to the pandemic, like many other mutual aid groups, STL Mutual Aid really came together as a response, but also kind of coming out of the Ferguson uprising, coming out of Solidarity Economy Movement, coming out of people working in social service agencies who were totally disillusioned with how the government and how nonprofits were going to respond to the pandemic. And the really important thing I think for me to lift up here is that mutual aid is the key to reaching the people that we need to build the solidarity economy. For me, it's been the missing link in: How do you create a space for many, many people, the number of people that we need to make this work, to have a home, to build a community, to learn, to do political education together, to train, to learn how to become organizers? How do we get everyday people to buy into these ideas and to see that all of these things are possible?

Deepa Iyer:

I want to turn back to you, Jessica. You've written this book about how Black communities practiced solidarity economies called Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice. Can you share a little bit about some of the highlights from the book?

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

Yes. It would be my pleasure. And thanks for mentioning the book. Yeah, it was at least 15 years in progress. So I talk about a strong but hidden history of mutual aid, cooperation, solidarity. Almost every Black leader, male or female, that we can talk about, I have found something that they had to do with either co-ops, or mutual aid, or some kind of solidarity economics because it wasn't ... Sometimes they couldn't even be involved politically if it wasn't for solidarity economics in the background supporting them in alternative ways so they couldn't be retaliated by in the current system. And often, it was because they had articulated that liberation really couldn't just be civil rights, getting to vote or something. But it really had to be about economic liberation.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

So some of my best, my favorite examples, just in terms of solidarity economics, you can think about the Underground Railroad. And most of the time, we think of it as just sort of a social thing. Right? People letting each other know that if you go here, these people can help you to the next thing. But actually, if you think about, it's a solidarity ecosystem, so it wasn't just about the communications and the social relations, you had to put people who had resources, like they had a house with a cellar that they could hide you, or they had a wagon that they could hide you in, or they had food that they could share with you. So there's economic elements in addition to the political, social, and geographic kind of thing. So you're moving people from bondage to freedom through this solidarity system.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

Then you can look at what was happening in the 1880s, and the backlash in the 1880s was the rise of white supremacy and the Jim Crow South. But it was a period when the populist movement, which also included a Black populist movement, the beginnings of organized labor and cooperative development are all happening together, and the same organizations were involved in all three. And then the 1930s was another really prolific period, especially now by that period, you could actually create official incorporated co-ops, and so Blacks as well as other groups, even with help from the FDR administration, were doing ag co-ops, worker co-ops, food co-ops, credit unions. One of the most prolific periods that I found, another big period was the '60s and '70s. The Black Panther Party was doing co-ops, so that's what I mean by this long, strong history.

Deepa Iyer:

Yeah. I want to thank you for doing that labor of unearthing the stories. Julia, I'm just curious. As you hear Jessica talk about this long history in Black communities, what's coming up for you in terms of how that relates to the work that you're doing in St. Louis, and sort of the broader work of the New Economy Coalition?

Julia Ho:

Well, first of all, I just want to say I can't overstate the importance that Collective Courage has had on kind of the cooperative economic movement and solidarity economy movement on our local work here in St. Louis. One thing I really love about the book is both the uncovering of histories and organizations that people might not have heard of, but also the connection to things that people do know, and thinking about, okay, the Black Panther Party, most people know about that. The civil rights movement, most people know about that. What they don't know is that hidden side of it, or that underground history of that all of these people did have some orientation to solidarity economics, to cooperative economics, even if they didn't call it that, for survival reasons, or even because that terminology didn't exist yet.

Deepa Iyer:

Yeah. And also, I can totally see how uncovering and sharing histories like this can be so inspiring, like you said, Julia. I'd love to dive a little bit deeper into both capitalism as a system, and also the nonprofit sector. So I'm wondering if, Jessica, you could start by giving us a bit of a framework around how to understand these two systems.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

So one of the reasons why in the solidarity economy, we keep talking about people over profit is because the current system, which I guess is 300 or 400 years old now, I guess 400 years old, maybe more, of capitalism is profits before people. Right? It's all about what we call profit maximization. And unfortunately, people are enamored with capitalism because it provides rapid growth and because it's really the only system we know officially, and it's the system that most of the people that we elect to government are trying to support. But the honest truth is if anybody was honest about it is that capitalism is killing us. It's killing us as human beings and it's killing our planet, and so it's really not sustainable.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

One of the ways I try to get people to think about this is we really have to, if we want sustainability as well as equity and prosperity for all, we've got to think about what we call a paradigm change, shifting the paradigm. And that's in part what the solidarity economy movement has been about, shifting that paradigm. First, showing us that we can live and survive and even prosper without capitalism, and two, showing us that while we're in the process of transitioning out of capitalism, we can be doing things that will help us.

Deepa Iyer:

And what about the nonprofit sector and the C3 formations? I wonder, Julia, if you want to talk about that a little bit. When I look at the sort of membership of The New Economy Coalition, one of the things that stood out to me is that there are so many different types of formations. Yes, there are some nonprofits, but there are also cooperatives. There are formations around food and farming, or land and housing, climate and energy. And I'm curious if you could talk a little bit about how these formations overcome some of the restrictions that we see when we think about a C3 sector.

Julia Ho:

Essentially, the solidarity economy movement is an invitation for people to practice liberation now. We don't have to wait until everything is perfect in the world. We can start to kind of plant those seeds now, and this is the time to do it. One way that the solidarity economy is trying to address this or trying to think creatively about this is by creating many different formations, like you mentioned, work of cooperatives of course are a way for workers to own their businesses and to own and to have power over them, over their work.

Julia Ho:

But there are also many different interesting things in the world of what we call transformative finance, or non extractive finance, or different ways that people are taking what are the traditional tools of investment and how do we change them and make them so that the people who are receiving those investments are actually benefiting from them, they are not being exploited, and that everybody, there's enough for everyone. So projects like [inaudible 00:17:32] Commons, projects like [inaudible 00:17:34] of Boston that are thinking of different ways for people to actually invest in these kinds of futures together and to profit together are really important.

Julia Ho:

I'm a member also of Resource Generation, and Resource Generation is a movement of young people, which is kind of specifically defined as 18 to 35, young people who have access to privilege and wealth, who are actively organizing for the redistribution of land, wealth, and power. And some of that is through philanthropy, giving the money away, that they know that they've inherited from this legacy of harm and slavery and all of these things. But some of it is also through transformative investment as well. And so there are communities of people out there that are doing this work and are a part of this solidarity economy.

Deepa Iyer:

And I will lift this up, but solidaryeconomyprinciples.org, that actually has been a resource that I've gone to time and again as well to understand what are the characteristics. And I also appreciate what you said, Julia, that it's really just about practicing, experimenting, trying something out, and then learning, and then changing direction as one needs to. So I appreciate how you said you don't have to wait for things to be ideal or perfect. And right now, as we are working through all of these overlapping crises that are facing people, whether it's the pandemic, or the recession, or obviously greater threat of white nationalism, I was wondering I you could both talk a little bit about how solidarity economies could be a strategy and a way for us to not just address the crises, but bring in a different way of living, supporting, thriving all together. So Jessica, maybe could start with you and then follow up with Julia.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

I think Julia said at the beginning, but we also know that sort of mutual aid and solidarity economics often are stimulated during a crisis. But we know they also last through a crisis and past a crisis. It's one of the reasons why some of the prolific periods that I found for Black co-ops were during crisis periods of some kind, working together, figuring it out together, pooling our resources, so I see that happening now. People are coming together for food security. Right? There's more food co-ops starting now than almost ever in history in almost every community, food co-ops and farmers' markets and urban agriculture, sharing of community gardens and things like that. So people again are trying to do whatever they can to make it work. And luckily, now they also have more language and organizations that can support them in how they do that.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

So I feel like the tools are out there, and it's the work of people like Julia and I and you to help people find where those tools are, to understand that their instincts are right, and that they should pursue those instincts and that there's places that can help them to connect them to other people and connect them to the skills that will help us to really perfect this stuff so we can keep moving on to the next level.

Deepa Iyer:

Absolutely. Julia, what about you? Are you seeing ways in which either in your work in St. Louis, or The New Economy Coalition as a whole that there are ways in which folks are responding to these crises right now in really collaborative ways?

Julia Ho:

I think the pandemic made a lot of people think about disability in a different way, disability justice, introduced people to this idea that actually, I may have thought that I was good and I was safe and secure in the society, but I'm just one paycheck away from being evicted. And what kind of conversations does that open up? It an either push people into hopelessness and despair, or it can motivate them and radicalize them into movement and action, which I think is what we're seeing a lot of happening. And I think one of the other really beautiful things about the solidarity economy movement that I think sets us apart from many other movements is that we welcome anything that you can offer. There's nothing within the realm of possibility of what it is that you as a person can do. There's no restriction of your abilities of you have to be able to be this type of person who does this type of thing in order for you to be part of this movement.

Julia Ho:

It's very open. One of the things that: What does it look like for you to live your full creative potential? And how can you do that in community with other people? That's essentially what we're asking people to do.

Deepa Iyer:

Thank you so much. I've learned so much from both of you. But also, recognizing that when we talk about solidarity economies, it's not restricted or relegated to a particular project and/or a particular campaign or goal, that it actually is an invitation for so many different people with different skillsets, different interests, to come together and figure out how to solve a particular problem in their community. Want to thank you both for what you do in terms of documenting, practicing, coordinating, communicating. And we will put all of the links that you all have spoken about in terms of both websites, as well as readings, and Jessica's book, of course, into our resource notes, so folks can get a copy of that as well.

Deepa Iyer:

So thank you so much for joining us. Thank you, Julia. Thank you, Jessica.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard:

Thanks. It's been a pleasure. Thanks so much.

Julia Ho:

Thank you, Deepa, so much.

Deepa Iyer:

I'm so grateful to Jessica and Julia for taking the time to join me for this month's episode. As I reflect on the work that we do at Solidarity Is This and Building Movement Project, it's so clear how solidarity economies embody the characteristics we identify when we think about transformative solidarity practice, like centering those in need, or finding connections and commonalities, being rooted in co liberation and building capacity. In a way, solidarity economies are already building the type of world that many of us want to live in.

Deepa Iyer:

I invite you to check out the notes for this podcast, which has links to the resources that Jessica and Julia shared, along with reflection questions. And I want to send a special shout out to my colleague at Solidarity Is and BMP, UyenThi Tran Myhre, for putting the resources together and supporting this podcast overall. Thank you to everyone for listening. Please share and subscribe to Solidarity Is This on your favorite podcast platform. And please check out our archive on www.solidarityis.org. Be well, everyone. Take good care of yourselves and the people in your ecosystems. Until next time, this is Deepa Iyer, and you've been listening to Solidarity is This.

ABOUT SOLIDARITY ECONOMIES

The New Economy Coalition defines the solidarity economy as “a global movement to build a just and sustainable economy where we prioritize people and the planet over endless profit and growth.” Solidarity economies are rooted in shared values including:

- solidarity, mutualism, and cooperation

- equity in all dimensions: race/ethnicity/nationality, class, gender, LGBTQ

- the primacy of social welfare over profits and the unfettered rule of the market

- sustainability

- social and economic democracy

- pluralism and organic approach, allowing for different forms in different contexts, and open to continual change driven from the bottom up

See more at The US Solidarity Economy Network.

Reflection questions after listening to the podcast:

- What are the ways in which you practice mutuality and connection already? For example, are you involved with barter and gift exchange, mutual aid, or a community childcare co-op?

- We heard Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard share some examples from her book, Collective Courage, on “a strong but hidden history of mutual aid, cooperation, solidarity” in Black communities, from the Underground Railroad to the Black Panthers and beyond. What additional examples can you think of from history that show how our communities have been practicing solidarity, even if by another name?

- In the podcast, Julia Ho says: "One of the purposes of a solidarity economy is to provide a space for people to survive through these crises, but also the rebuild the way that we want society to look.” Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard adds: "mutual aid and solidarity economics often are stimulated during a crisis. But we know they also last through a crisis and past a crisis." How do you notice people practicing solidarity during our collective crises as a way to pre-determine the world we want to see?

Resources:

- Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice | In Collective Courage, Jessica Gordon Nembhard chronicles African American cooperative business ownership and its place in the movements for Black civil rights and economic equality.

- System Change: A Basic Primer to the Solidarity Economy (Nonprofit Quarterly) Published during the first summer of the pandemic and the racial justice uprisings in 2020, this primer is a great place to learn more about what we’re leaving behind (capitalism) and what we’re moving towards (post-capitalism and solidarity economy).

- Can solidarity economies fix everything capitalism has broken? An intro to solidarity economics as another path forward. Related: an intro to racial capitalism, a zine written and illustrated to make accessible the theories of Black Marxist and prison abolitionist scholars including Cedric Robinson, Robin D.G. Kelley, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Mariame Kaba, Angela Davis and others.

- Solidarity Economics: The Mini-Comic Chris Benner and Dr. Manuel Pastor’s Solidarity Economics is visualized in a mini comic. This comic highlights central aspects to understanding solidarity economics and implementing the approach to your own communities.

- Learn more about solidarity economies across the U.S., including Cooperative Economics Alliance of New York City, Kola Nut Collaborative in Chicago, Cooperation Jackson in Mississippi, Cooperation Humboldt in California, and Wellspring Cooperative in Massachusetts.

- Solidarity Economy Principles: practices and resources to learn more about solidarity economies.

- Seed Commons is a national network of locally rooted, non-extractive loan funds that brings the power of big finance under community control.

- Resource Generation is a multiracial membership community of young people (18-35) with wealth and/or class privilege committed to the equitable distribution of wealth, land, and power