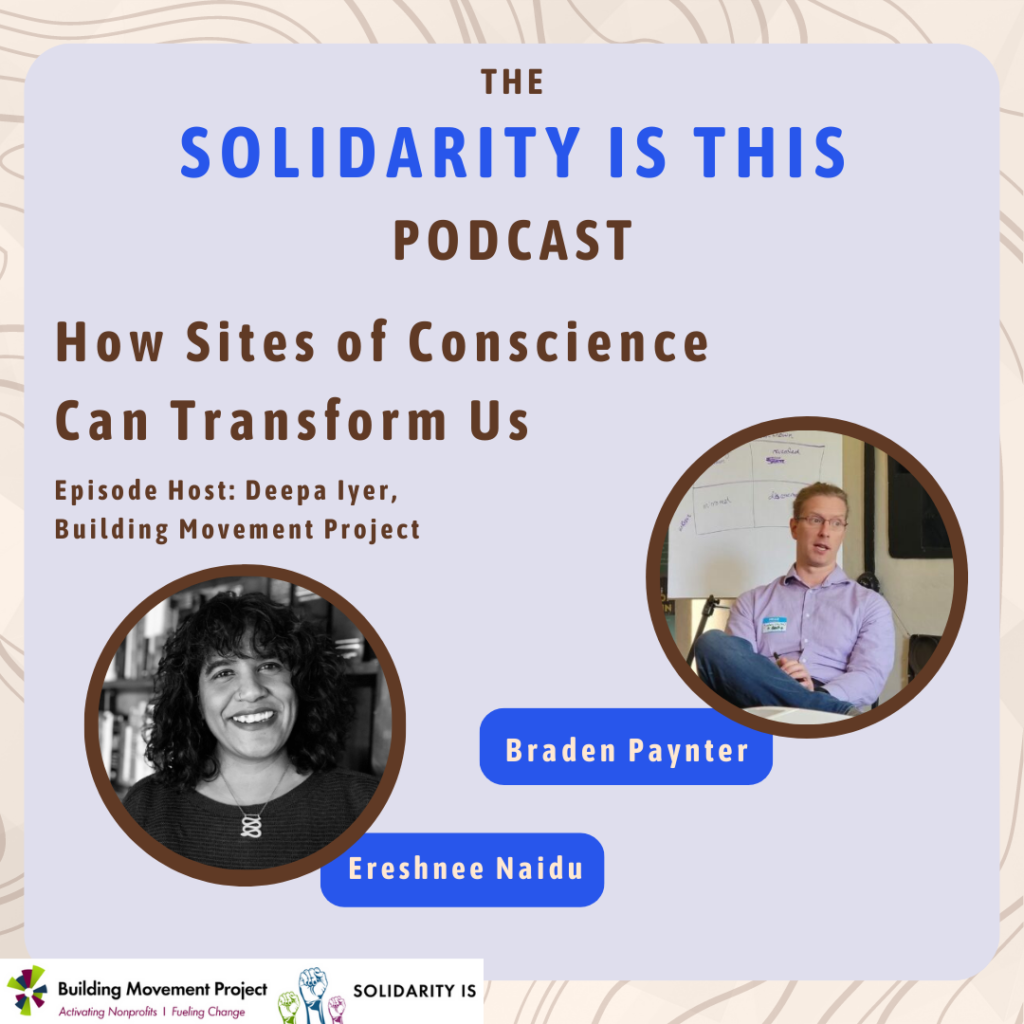

How Sites of Conscience Can Transform Us

The new season of Solidarity Is This begins with an introduction to the power of sites of conscience. Host Deepa Iyer speaks with Braden Paynter and Ereshnee Naidu at the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience.

About the Guests

Ereshnee Naidu is the Senior Director for the Global Initiative for Justice, Truth and, Reconciliation, ICSC’s flagship program on transitional justice. Ereshnee has over twenty years of experience designing and implementing community outreach strategies and programs in critical post-conflict settings that include South Africa, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, and Colombia, among many others. She is a seasoned educator with extensive curriculum and workshop design experience, and has broad content development, training, and facilitation skills.

Braden Paynter serves as the Director for Methodology and Practice at the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. He leads the Methodology and Practice team in supporting member development of programming, exhibitions, and engagement strategies that address their communities’ most pressing challenges. Braden has personally trained hundreds of organizations in dialogue, community engagement, planning, and operating at the intersection of history and justice. Before joining ICSC, Braden worked with the National Park Service at the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site where he oversaw public, education, and professional development programs and in exhibits at Old Sturbridge Village.

More and more communities are turning to memory and memorialization as practices for justice and recognition and acknowledgement about what they went through.

Ereshnee Naidu

Deepa Iyer:

Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Solidarity Is This podcast, an initiative of the Building Movement Project. I'm your host, Deepa Iyer. We're so excited to launch this new season of the podcast which will examine how sites of history and memory can transform ourselves and our communities, can deepen our solidarity, and build towards a more just society. This episode titled How Sites of Conscience Can Transform Us is a great introduction to our new season, because our guests, Braden Paynter and Ereshnee Naidu, set the stage for how projects, whether they're large museums or small community initiated ones, can become really powerful experiences for the public leading to a more truthful understanding of history, courageous conversations and deeper solidarity, the preservation of memory, and even healing injustice for community members harmed by the state.

Both Braden and Ereshnee work at the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, which is the only worldwide network dedicated to transforming places that preserve the past into spaces that promote civic action. Braden is the Director for Methodology and Practice there. He helps good ideas move around the world by helping sites build knowledge, skills, and relationships. Ereshnee is the director for the Global Initiative for Justice, Truth, and Reconciliation. She has over 20 years of experience designing and implementing community outreach strategies and programs in critical post-conflict settings around the world. Braden and Ereshnee, welcome to the Solidarity Is This podcast.

Ereshnee Naidu:

Thank you.

Braden Paynter:

Thank you so much.

Deepa Iyer:

I want to start by asking each of you about your catalyst for engaging in social change work. Why don't we start with Ereshnee first?

Ereshnee Naidu:

I started very early on in my career working in theater and working particularly with women who were survivors of domestic violence using Augusto Boal's Theatre of the Oppressed Technique. I found that in order for these women to be held by the community and to feel safe, it was necessary to include the community. I think that any kind of activism work begins from the bottom up, from a community level, and that ensures sustainability and ownership. That's the premise of lots of our work as the Global Initiative for Justice, Truth, and Reconciliation. I currently manage that program, the GIJTR program at the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience.

Deepa Iyer:

That's so great to hear how you got started and realized the importance of community participation so early. But Braden, also want to ask you, what is your point of entry into this work and how did it land you where you are today?

Braden Paynter:

It very much starts for me with my parents. My dad was an anthropologist who believed that the tools of anthropology should be turned back on North America and Europe to try and understand these worlds. He worked with race, and class, and gender in New England. My mom was a direct action lawyer working on housing. You put those two things together and you get a public historian. I started working in museums and historic sites, and I noticed this really big divide between why the historic sites thought they were there to talk about 19th century farming practices and these really important changes in agricultural markets in 1825, and the reasons that people were coming, which is that they were running out of green space in the rest of their life, or they were on a date and wanted to look really impressive, or they needed a place where their kid to run around.

It made me really interested in how we can better use these powerful places to take on the biggest challenges of the present. That led me to work for the National Park Service for about five years at the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in Washington, D.C. From there, I joined the coalition where I'm the Director of Methodology and Practice.

Deepa Iyer:

That's great. I loved hearing about your upbringing, and obviously, totally understand how you turned out to be who you are based on that. Ereshnee, I want to start with you. Can you share a little bit about how, going back to community participation and citizen engagement, how does that connect with this conscious effort to use memory and history as ways to understand injustice in not just this country, but obviously, you work on a global level?

Ereshnee Naidu:

Over the years, we've also found that more and more communities are turning to memory and memorialization as practices for justice, and recognition, and acknowledgement about what they went through. For example, in Sierra Leone a while back, the coalition worked on the Sierra Leone Peace Museum. Just soon after the conflict, Sierra Leone had a true commission as well as a court, and people were afraid to go to the court to testify because it was a formal court. People didn't come forward. We found when we started working on the Peace Museum, that was the time when people started coming forward with artifacts related to the war, sharing testimony and stories that they had not shared at all at the Truth Commission or at the court. That's one example of how communities trust these initiatives.

Deepa Iyer:

Thank you, and I really appreciate the examples as well. Turning to you, Braden, one of the things that came up when Ereshnee was talking was the limitations of these state-endorsed projects on truth and reconciliation. You talked earlier about how traditional historical sites can be places where history is revised or it can be hidden. I'm curious about the sites that you work with, how they end up being focused on telling community histories, and then what does that lead to? Does it lead to repair? Does it lead to solidarity? Does it lead to awareness?

Braden Paynter:

A few ways that I think sites start to wrestle with that is they think about how to try and have impact with their site, and one very much is telling accurate and inclusive history of the past, what you were referencing. But there's a whole second part of that about who we're hoping hears that, who's involved in the creation of that, who's involved in the research, who's involved in the development of that, in the process of the telling, of the finding and of the telling, and then who are we hoping listens to that. We see people use history and historic sites in different ways. Just earlier today, we were talking with two sites, the Clotilda Descendants Association and then the James Madison's Montpelier. Thinking about the descendant association there and the Clotilda, for folks who haven't run across them, that was the last known ship that brought enslaved Africans to the continental United States with the intention of bringing people into enslavement.

It's their descendants' association right now. Sometimes these conversations are about internal support between folks, but it also takes a tremendous amount of trust to get folks to hear new information that's challenging to them and difficult for them. Some of this process is about building information, but a lot of this whole process is also about building spaces and relationships that support people in their ability to trust each other, to trust each other enough to hear information that might be challenging to support of their identity.

Deepa Iyer:

That's great. You answered a very complex question in lots of different ways that we can take it, so thank you. I wanted to turn to you, Ereshnee, because we've heard both of you share a number of phrases that have been writing down around sites of conscience and what their impact can be. History, memory, accountability, repair, trust. I wanted to ask you about healing and how these sites can often lead to community healing or even perhaps public healing. Can you talk a little bit about that process and why it's so meaningful and significant?

Ereshnee Naidu:

We've worked over the years. We've always heard from survivors and communities who are part of conflict that they marginalized... Survivors have said to us, "All I want is for somebody to listen to my story." It's just that listening in some way that somebody is acknowledging what you went through, that's the first steps towards some kind of individual healing, but I think with lots of memory work. For example, we've done some work in Columbia with families of the disappeared, where the families work together to make these dolls of the disappeared person. They were like little puppets and they put it in a recording to tell the story of the person's life. It was the younger generation that was listening to it. The other methodology that we use quite a bit is body mapping, so where survivors map out these beautiful artworks of the entire body. On the body, they identify points of trauma, places that gave them hope.

It's a hopeful process, because at the end, they actually talk about what's their hopes for the future. But these kind of projects allow survivors to be able to engage with their own trauma, as well as able to speak about it. It forms a sense of community in that way, highlighting for survivors that they're not really alone, that other people have gone through the same process with them. We've also done this in so many countries. People are able to feel a sense of community that we've all gone through this, and working on it together brings some personal acknowledgement, which contributes to healing. Also a form of justice, because it's a platform for them to be able to tell their stories. Therefore for many survivors, that in itself is a form of justice. I also think it also builds resilience in some ways.

Deepa Iyer:

I'm curious as to how projects and people work with you all. Ereshnee, could you start by telling us the process and methodology on your end?

Ereshnee Naidu:

I've been at the coalition for quite a long time and I've played different roles at the coalition. One of the things we found is that, at the very beginning, we had lots of museums, memory projects that were part of the network. Increasingly, we found coming from the Middle East and North Africa region, Africa, Asia, Latin America, that it was human rights organizations that were reaching out to us wanting to be members. That came, again, from a recognition that survivors were more and more wanting to engage in memory processes for various reasons.

For the Global Initiative for Justice, Truth, and Reconciliation, we're a consortium of nine international partners that work on transitional justice in a multidisciplinary and holistic way. Initially, transitional justice was, as it evolved as a field, focused a lot on the rule of law. That's a gap in the field and continues to be a gap in the field. The goal for our project is to include things like psychosocial support for survivors, forensics, truth telling that isn't just for accountability purposes but for awareness raising, acknowledgement, recognition, the things I mentioned earlier. From there, we reach out to other organizations who are not members who could contribute to the project.

Deepa Iyer:

For folks who might not be aware, can you give us an understanding of transitional justice?

Ereshnee Naidu:

Transitional justice are mechanisms that are put into place to address the past, whether it was the past of authoritarianism or of conflict. These mechanisms include truth telling mechanisms like truth commission, trials, tribunals. It includes institutional reform, like reforming the justice system, the police, the military. It also includes prosecutions, so accountability mechanisms, and finally, reparation. Things like symbolic reparations, compensation, restitution. In the U.S., there's a misconception that reparations is about money and about compensation, but it goes further than that. As I said, symbolic reparations, restitution, rehabilitation, so including psychosocial supports, services for survivors. All this is towards a goal of reinstating the rule of law and rebuilding a society that's based on trust. It aims to rebuild that relationship between the state, if the state was the perpetrator, and citizen, and also reintegrate and build trust between the state and the citizen.

Deepa Iyer:

Braden, I want to ask you a similar question, which is you do methodology, you work with projects, primarily, I believe, in the U.S., so how do you go about that?

Braden Paynter:

One of the foundational ways that folks work with us is as members of the coalition. That is, at its root, about being part of a network and having relationships and support with people around the world. Folks often reach out to us and say, "Hey, there is some challenge that we are facing as an institution." It's often around some kind of story that's really challenging for them to tell. We have an exhibit coming up that we don't know what to do with. Our staff are getting pushback because when they talk about the history of enslavement in the United States, they are getting people who are getting angry and emotional with them and attacking them in some way, verbally typically. How do we do this? We do training for folks in dialogue and dialogic interpretation and how that works in exhibits. We work with folks on curiosity and creativity as well, because we think that's actually a big part of taking on a wide range of these. A lot of skills on communication and relationship and partnership as well.

We also try and make sure that there is almost all of these projects need focus as well on relationships and on systems if they're going to survive and really have the impact that folks want, because we have so many different kinds of people involved in this. Parks, museums, historic sites, places of memory, small memory initiatives, everywhere, that it's not all places with big columns on the front. It's absolutely places like middle passage port markers and ceremonies project, where they're going around trying to mark every place that enslaved Africans were landed in the United States and hold ceremonies there, but that's not something where they control a lot of land. They're trying to be an ignition point for local communities to figure out the right way to do that for them. This moves in all kinds of scales and these institutions look really different across the country.

Deepa Iyer:

Yeah, that's great. It's good to hear that it's not just the places with the columns in front of them. I'm curious about this moment in time. Are you seeing a pushback on these projects that are preserving memory and history?

Braden Paynter:

Absolutely. It's happening. There is a really strong and visible struggle to try and shape our understanding of the past in the United States right now. That is something that is particularly heightened in this moment. Every one of these public history conversations, yes, is about the past, but it's also about the present, and the ability to shape that present, and the ability to shape the future. When we talk about what monument we want to have in our downtown spaces, that is a conversation about the story we want to tell of who we were, who we are, and try and shape people's ability to conceive of who we can even be. This is another place to go back to the title of your podcast and think about solidarity. The U.S. isn't the only place where teachers and public historians have found themselves under this kind of pressure. We're just trying to figure out how to get some teachers from Turkey in conversation with teachers from Florida to talk about what it means to operate when your government doesn't support you.

Deepa Iyer:

Yeah, thank you. I really appreciate you bringing solidarity back into the conversation because all of the concepts we've talked about are connected to how solidarity builds and grows. Tell us about a site that means a lot to you personally and why.

Ereshnee Naidu:

One is Constitution Hill in South Africa, and that's because I am South African, but I got to work very closely on developing the Constitution Hill site. That was my first experience of consultation. I worked on the community consultations. The site that's in the middle of an urban city center with one side is the city, another side, a university community, and another side is an immigrant community, and on the fourth side is a suburb. We consulted so extensively with everybody from academics to group vendors, as well as sex workers working in the immigrant communities. But what I learned from there was that consultation can be as extensive, but you also have to give people parameters when they're making a decision. Because when we asked people what they wanted at the site, they wanted everything from a zoo to a swimming pool and a hairdressing salon.

Deepa Iyer:

What did it end up as?

Ereshnee Naidu:

Now the site has become a space for cultural resistance, for dialogue around gender issues, but also to appeal to the younger generation. Things like Afro Punk have been held there, and it was a former prison site where Nelson Mandela was also imprisoned. It was all about transforming the meaning of the space, but also making it very salient for a current generation. That's my favorite site, that one.

Deepa Iyer:

Great. That sounds lovely and very powerful, and I can see why it means a lot to you too.

Ereshnee Naidu:

Thank you.

Braden Paynter:

A site that has been very much on my mind lately because of a way it was helping me grow is President Lincoln's Cottage in Washington, D.C. It was the Lincoln's retreat from the White House. It's where Lincoln likely did most of his writing of the Emancipation Proclamation. It's been a place that I've was connected to when I was at the Douglas House and long thought the kind of work and storytelling they do is really strong there. But the team there has an exhibit right now that is about grief and child loss. It's an example of how when we ask inclusive questions about the past, it helps us have different kinds of conversations and relationships in the present. The historical narrative of Mary Todd Lincoln is often one of this somewhat hysterical woman and this flighty woman and this rape. They've reframed that as a woman who has lost her child and is thinking about grieving around that.

Using the Lincolns as a starting point for understanding the grief of parents who have lost children opened up an opportunity for them to work with parents today who have lost children for a variety of reasons. The conversations that I got to have around grief because of that, what it opened up, has helped me as my dad passed away recently and he was this deep and important person for me. Knowing that there's both a set of stories and a set of people and a place that I can go to think about those things when I don't think that can happen any place else has been important to me lately.

Deepa Iyer:

Thank you, Braden. Thank you for sharing that. I'm sending you care and support. I know you've been going through this hard, hard time. I also appreciate you linking it to this work and how it can also lead to some personal transformation. I have to say that I will need to take a trip to that cottage. I live in the D.C. Area and I've never been there, but you've given me a recent to go. Where can people find you all online?

Braden Paynter:

Yes. Sitesofconscience.org, there's resources from the member sites that are freely available there and from us. There are regular webinars that are free. We'd love to talk to everybody who is interested in trying to move this work forward wherever you are.

Deepa Iyer:

To close, thank you so much, Ereshnee, for joining us.

Ereshnee Naidu:

Thank you, Deepa, for having the conversation, and I look forward to talking more soon.

Deepa Iyer:

Thank you so much, Braden, for being part of the podcast.

Braden Paynter:

Thanks for having me. Thanks to you, Deepa, for all the work that you do, having this podcast, the organization pushing this out, and to all the people who are listening and are making this a part of what they do every day. Thanks to you all as well.

Deepa Iyer:

I am so grateful to Ereshnee and Braden for joining us on the Solidarity Is This podcast. Please check out their important work at www.sitesofconscience.org, and perhaps you'll find a point of entry to partner with them on a place of memory and history that you want to preserve or transform. We would also love to hear from you about these projects, projects that preserve history, memory, and solidarity that we should be aware of. Please drop us a line and let us know. You can reach out to us via www.solidarityis.org where you'll find past episodes of this podcast, as well as information about solidarity principles and stories. Please also make sure to subscribe to Solidarity Is This so you know when the next episode drops. As always, take good care of yourselves and your communities. We'll see you next time on Solidarity Is This.

Resources

"The need to remember often competes with the equally strong pressure to forget. Even with the best of intentions – such as to promote reconciliation after trauma by “turning the page” – erasing the past can prevent new generations from learning critical lessons and destroy opportunities to establish peace now and well into the future.

A Site of Conscience is a place of memory – such as a historic site, place-based museum or memorial – that prevents this erasure from happening in order to foster more just and humane societies today. Not only do Sites of Conscience provide safe spaces to remember and preserve even the most traumatic memories, but they enable their visitors to make connections between the past and related contemporary human rights issues."

- International Coalition of Sites of Conscience

- Every year, the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience hosts dozens of webinars, workshops, and trainings focused on urgent topics related to memorialization, human rights, transitional justice, museums, historic sites, and much more. See upcoming events and check out past recordings and resources here, and learn more about working with the Coalition on a training here.

Reflection Questions After Listening to the Podcast

- Ereshnee shares how memory work can support survivors of violence with healing, from finding community and building resilience and to serving as a form of justice. How do you see this work expanding what "justice" typically means?

- We heard Braden say: "When we talk about what monument we want to have in our downtown spaces, that is a conversation about the story we want to tell of who we were." What stories are being told in the public spaces in your hometown, whether that is a monument in a downtown neighborhood, a public library, building names on a college campus, or otherwise?