Solidarity Narratives in Crises: A Practice Guide

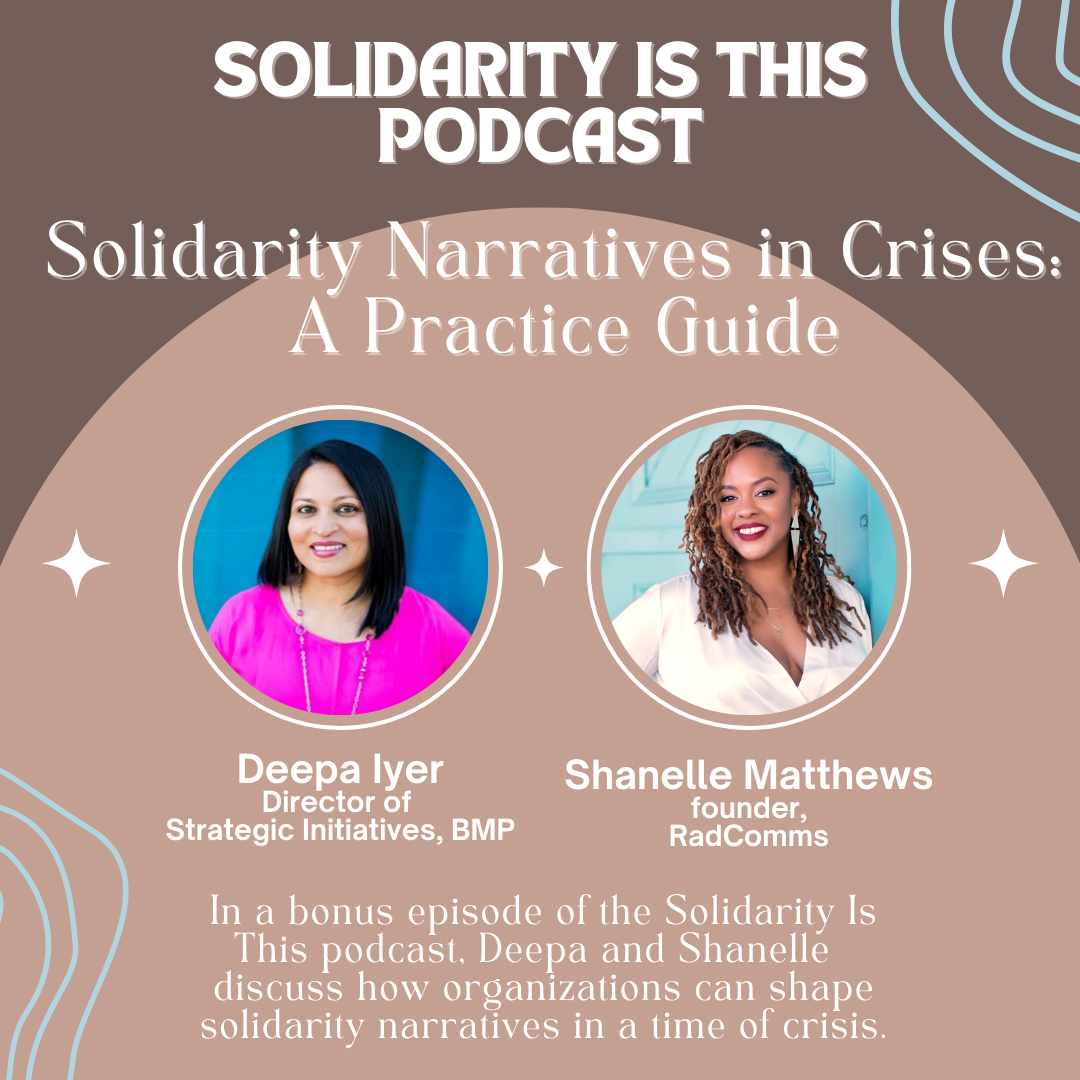

In this bonus episode of the Solidarity Is This podcast, Shanelle Matthews, founder of RadComms, joins host Deepa Iyer to discuss how organizations can shape solidarity narratives in a time of crisis.

About the episode guest

Shanelle Matthews

Shanelle Matthews collaborates with social justice activists, organizations, and campaigns to inspire action and build narrative power for social justice and liberation. She recently completed her tenure as the Movement for Black Lives communications director. She founded Radical Communicators Network (RadComms)—a global community of practice for social movement communications workers, and is a former faculty of Resistance Narratives at The New School. Shanelle is a Distinguished Lecturer at City College at the City University of New York. She is co-editor of a forthcoming anthology that details world-building narrative campaigns and strategies led by social movement communications workers in the 21st century.

If you're jumping on a bandwagon, if you're doing so because it's widely accepted or popular or perceived as being on the winning side, but you have not done the political study, values clarification, or personal work of distancing yourself from oppressive forces, it's going to be very hard for you to stand in your integrity in the face of critique.

- Shanelle Matthews

UyenThi:

Hello everyone. This is UyenThi Tran Myhre at the Building Movement Project. I'm excited to introduce this bonus episode of Solidarity Is This, featuring a conversation originally on Instagram Live, between BMP's Deepa Iyer and Shanelle Matthews, Founder of the RadComms Network and a distinguished lecturer at The City College of New York.

This episode comes to you in the midst of so much turmoil happening in the world, that we are grappling with as individuals and as an organization that supports movement leaders in the nonprofit sector. One of the themes that we began to notice is how organizations were struggling to identify solidarity narratives that were rooted in their values and their partnerships.

In this episode, you'll hear Deepa and Shanelle discuss different frameworks and a series of steps that organizations can follow during this challenging time to develop statements, build relationships, and extend deep and meaningful solidarity. As with all our episodes, this one provides ideas and experiences, that may or may not resonate with you. We invite you to listen, sit with any discomfort you might feel, and identify what aligns with your own practices as a leader and organization committed to solidarity. Here's the conversation between Deepa and Shanelle.

Deepa:

My name is Deepa Iyer, and I'm with the Building Movement Project. And for those of you who might be new to us, BMP is a national nonprofit that catalyzes social change through research and reports, through accessible tools, resources, and narratives, and by fostering deep relationships between organizations and movements. And my specific perch is to work on the Solidarity Is program, with my colleagues, Adaku Utah and UyenThi Tran Myhre. That is what we're going to be talking about today. We're going to be talking about solidarity narratives, and someone who has been steeped in thinking about solidarity narratives and narratives generally, the power of narratives, Shanelle Matthews. Hi, Shanelle.

Shanelle:

Hi, Deepa.

Deepa:

I want to thank you for joining us, and we're having this conversation during a time of tremendous grief and pain and overwhelm, due to the events that have been going on this past month, since October 7th, that have gripped the world. And I think that a lot of us are thinking about the hostages that were taken in Israel. We are thinking about the 10,000 plus Palestinians who have been killed at the hands of the Israeli military, including an unfathomable number of children. Usually, in moments of crisis, and we were prepping about this, Shanelle, we noticed that solidarity comes really easily in times of crisis often, but in this moment, we, at Building Movement Project and Solidarity Is, have been really thinking about the risk and controversy that is also surrounding it.

So we're hoping to get into the why and how of creating values aligned solidarity narratives, the power of narrative, process steps to design narrative strategies, and ways to deal with pushback. I'm grateful that Shanelle will help us unpack that. So just a brief introduction to Shanelle, and we'll get started. Shanelle is a longtime supporter of activist organizations and campaigns to build narrative power for social justice and liberation. She recently completed her tenure as the Movement for Black Lives' Communications Director. She also founded Radical Communicators Network, also known as RadComms, a global community of practice for social movement communications workers. She's the incoming distinguished lecturer at City College, at The City University of New York, where she teaches and writes. And I think I'm just going to get started by asking you a little bit about your journey to support organizations and people with narratives.

Shanelle:

Well, thank you, Deepa, and thank you to the entire Building Movement Project team who helps to organize this. In 2016, when Trump was elected, I wrote asking communications workers, what were we going to do, in terms of ensuring he didn't get reelected? Shortly after that, I ended up organizing a call where 100 people joined, and we talked about, we commiserated together, just shared in our grief and our pain and our frustration, and talked about what we wanted to do. And at the end of that call, I asked people, what do they need, in order to do what we said we were going to do? They said they needed a network, a place for communications workers from the grassroots sector, people who were traditionally excluded out of nonprofit establishment spaces, who were talking about the most radical ideas of our time. RadComms exists to do three things.

We believe that, for social justice communicators to be powerful, we must be organized and invested and inspired and accounted for. And RadComms was established to inspire a more complete approach to movement building among left-leaning and progressive communications workers to democratize our work. And to do that, we provide a narrative infrastructure through community of practice for emerging and experienced left and progressive communications workers and also others. And our goal is really to build narrative power for radical ideas and just to demystify community of practices really for people who come together voluntarily, who share common interest, discipline, domains of knowledge, and engage in regular interactions. The sharpening part really comes from our movement legacies and lineages and how we understand our role as movement workers. We also provide peer to peer learning and political education. The third thing that we do, which to me is just the most important, is that we radicalize and politicize movement workers around narrative power.

So as challengers of dominant and oppressive ideologies, our communication strategies must be rigorous, they must inoculate us against the status quo of power and privilege, they must inoculate us against cooptation. And so, one way that we do this is by ensuring that our organizations and our coalitions and our movements use a narrative framework that builds ideological power for a liberatory society. We want people to adopt a power-based framework for social justice communications, because it directly addresses power imbalances, often at the heart of oppression, dehumanization, and social injustices. And we believe that such a framework recognized isn't just about conveying information, but it's also challenging the fundamental legitimacy and reshaping entrenched power structures. And this is really a departure from mainstream communications work.

Deepa:

I really appreciate how you made the distinction between narrative and communications and also, how it's all about challenging the dominant ideologies and the power imbalances, that that's the power of narrative. So let's get into this idea of solidarity narrative. So to us at BMP and Solidarity Is, we really think of "solidarity" as a verb. It's a set of actions that are practiced over and over again to show that we're aligned with a cause or a campaign or a call to action or even a community. I know a lot of people have talked about solidarity as transactional and transformative. And transformative solidarity is the type of solidarity that changes you, so it could change your action, your behavior, your belief as a person. But beyond that, getting to the power part, it would change a policy or an institution. But I'd love to turn it to you to talk a little bit about how solidarity can be a powerful narrative and what it takes to go beyond the narrative of "I stand with" or "we believe in" to actual change.

Shanelle:

Yeah, thank you for that really beautiful definition of solidarity. I also want to say, I have more questions than I do answers these days. So a narrative is really the representation or a specific manifestation of a story, the actual way that the sequence of events is presented to the audience. It can be considered the kind of structure or framework that holds or conveys the story, encompassing the choice of point of view, the sequencing, or any kind of additional commentary that person's going to add or people are going to add to it. It dictates really how the story is told. On the other hand, stories are linear. They have a beginning, a middle, and an end. And they often recount a series of events. They have a protagonist, they have a problem, they have a path, and they have some kind of payoff. And so, a helpful rhetorical device to remember this, that I also learned from the narrative initiative, is that what tiles are to mosaics, stories are the narratives, the relationship is symbiotic.

Stories bring narratives to life by making them relatable and accessible, while narratives infuse stories with deeper meaning. So storytelling is the tactic that we use. And narrative change is actually the goal. So while a story is really about what happens, events, characters, conflict, a narrative is more about how the story is presented or structured, perspective, sequencing, and style. So on the interplay between solidarity and narrative, one way to think about how solidarity narratives emerge is knit through narrative weaving. So narrative weaving really refers to the art and technique of crafting and interconnecting multiple storylines, themes, or elements, to create a cohesive and compelling narrative. So inside of this narrative, weaving inside of our solidarity narratives, you're going to have multiple storylines. Some of them may be kind of complex, and some of them less so. They're going to intersect, they're going to influence each other through this narrative weaving, even if they seem unrelated.

So I do have some questions I wanted to pose to suggest to people when they're developing their solidarity narratives, because I think that, again, having more questions and answers in these moments means that we'll just be more clear at the end of our statement writing. If you're writing a solidarity statement, you want to ask yourself, one, "What pre-work have we done, [inaudible 00:09:35] organization, to prepare us to articulate a value aligned statement right now? Where's the agreement? And where's their disagreement?" Two, "Why are we writing this? Do we feel pressured? Or is it coming from a place of authenticity? Is it coming from a genuine place? What process do we have in place to do this? How do we make decisions where there necessarily isn't alignment? How do we contend with internal conflict, in the event that it surfaces? What stories can we tell that illustrate the complex systems at play in these shared liberatory struggles?

How can we be explicit about where the blame lies and who is responsible for the transformative change that needs to happen? What values are central to this issue? Do we have clear understanding of the problem? Do we have clear understanding of the solutions that are being posited? Are we asking people to take action? If so, what action are we asking people to take? If there is no immediate action, how can we paint a picture of the impact? If the solution is realized, what then becomes more true? What assumptions allow the dominant and oppressive story to operate as truth in these public discourse? And how can we undermine the basic legitimacy of those assumptions? How can we incorporate historical context into this statement to ground it in the social reality and material conditions of those targeted by oppression and domination? And then, finally, after publishing, can we stand in our integrity and our power and back our statement up, even at the risk of criticism or at the risk of losing supporters or even funders?"

Deepa:

Thank you for that list. That is a really, I think, easy to understand list, that folks can go through as a roadmap to think about, when they're crafting or developing their solidarity statements. Can you talk a little bit about what happens when there is that pushback, when there is that critique? And I ask this, because we're really seeing this now. We've been trying to work with and support organizations that want to stand in solidarity in this moment and that are trying to craft statements that are complex and nuanced. And at least I feel, and I'd love to know if you think this, is that we're in a time when we're forced into these binaries, so we have to be pro or anti, or we're forced into understanding very complex issues and historical issues as conflations, where critiquing a government is tantamount to critiquing a faith or a people.

So these sorts of markers that are put out there, I think, make it tough for organizations to figure out, how are they going to put out a balanced and empathetic statement, a call to action? And we hear organizations say that they are afraid of losing donors and supporters and getting critiqued. And as you know, I think we were sharing some of this, we're seeing this play out where organizations have to retract their statement, delete all their tweets, because the silencing right now and the doxxing of folks who are talking about a ceasefire, for example, is rather intense and is happening around the country. So how do organizations, who are trying to figure that out, deal with any pushback?

Shanelle:

I'm learning a lot as I practice my solidarity, and I'm also learning how to navigate some of these harder questions about "nuance." And so, nuance has become one of those words that sometimes I don't feel like it means anything because it's so overused. I want to talk about how nuance is weaponized to manipulate, to deceive, or to achieve specific political goals, in most decolonial or revolutionary struggles. There are many ways nuance can actually be weaponized, but I'm going to point out six of them. They include selective framing, divide and conquer, scapegoating, false equivalency, whataboutism, and gaslighting. And I'm going to break those down for everybody. So first, selective framing. So what is it? It's the deliberately emphasizing or deemphasizing certain aspects of multifaceted issues to manipulate perceptions, like selectively presenting facts or using half truths to shape a narrative that serve a particular agenda. So this includes selectively choosing data statistics or examples that support a particular viewpoint, while ignoring or dismissing information that contradicts it.

The second is divide and conquer approach, which means exploiting differences within oppressed groups to sow discord, weaken collective action or solidarity, and pit people against each other. The third is scapegoating, which happens when oppressors blame oppressed groups or individuals for complex societal issues or problems, oversimplifying the causes and diverting attention from underlying structural systemic factors. We've seen this in the US. Empires are so good at this. The fourth is false equivalency, which means drawing false parallels between two disparate actions to create the illusion of moral equivalence. We want to refrain from invoking a kind of two sides narrative. Each time we discuss Gaza or Palestine, the situation is inherently imbalanced.

And another false equivalency is that opposition to the political movement of Zionism or the policies of the state of Israel or support for Palestinian sovereignty and the end of the occupation and genocide are anti-Semitic, when, in fact, as our friends at Jewish Voices for Peace have continued to repeat, opposition to Zionism is no different from criticism of any other political ideology or policies of any other nation state, such as the cellular colonialism, imperialism, white supremacy found in the United States.

And number five is whataboutism. Whataboutism, the tactic of responding to criticism or accusations by deflecting attention to unrelated issues or past actions of the accuser, thereby avoiding accountability for one's own actions or decision. Empires and their sympathizers are well practiced at whataboutism. And finally, number six is gaslighting. We've seen this a lot, right? So this means manipulating people's perceptions of reality by selectively presenting information or events in a way that makes them doubt their own memory, their own judgment, their own sanity.

Deepa:

Thank you so much for laying those six. Obviously, with everything that you just said, Shanelle, we're having this conversation because we're hoping that organizations will listen to this and others and take what aligns with them, take what aligns with their values, and have a critical lens, in terms of what it is that they want to put out, but not saying what they should put out, but that they should take the information and make some decisions internally about what makes sense for them. But in terms of some of the powerful narratives that have come out, some of the ones that we've seen are really clear examples of Asian-American organizations making the link and the connection between war and militarism and experiences of those with their communities. Another was, and I think folks know about this, is the statement that came out from Black organizers and artists and leaders, Black4Palestine, which makes very different connections around occupation and around injustice.

I wanted to also ask you a little bit about beyond a crisis moment, because narratives oftentimes, I think, are sparked during a time of crisis. How do organizations build a narrative in a time of crisis though? I don't think it's always easy to do that. If you're trying to actually put out the statement or put out the call to action, how can organizations pull that together, especially if they don't have RadComms or any comm staff? We work with a lot of small organizations that are under-resourced. Can you share a little bit, in terms of either resources or process steps for organizations to do that?

Shanelle:

We should actually ask ourselves, "What is our organizational positionality in this moment? Have we done our values clarification? What is the process by which we actually..." Those questions I asked earlier, "How do we arrive at the place?" And in times like this, there's a phenomenon in which individuals or groups align themselves with things that are popular, dominant trends, opinions, courses of action, simply because they're widely accepted or they see their friends doing it or other organizations doing it or they feel the pressure.

Deepa:

Feel the pressure.

Shanelle:

And in my view, there will inevitably be instances where not everyone agrees consistently engaged in the process of clarifying your shared views, your principles, and political education. It should not come as a surprise to your base when you issue a statement that reaffirms the values that you have collectively embraced. And it's also important to remember that, during these times, a fissuring can happen, that individuals and groups might separate or split based on their beliefs, and that is actually okay.

And in the meantime, individuals can take action. But to your earlier question about how we contend with the critique, if we put it out and we get pushback, and then, also, I'll say something about under-resourced or under capacity groups, the critique part is going to happen no matter what. It doesn't matter what issue you're talking about. And this is why it's so important for organizations to be very clear in their integrity and their principles and their values and their movement lineage. Because critique and pushback actually land differently on the nervous system if you are grounded in your politic and grounded in your movement practice. That's to say, if you're jumping on a bandwagon, if you're doing so because it's widely accepted or popular or perceived as being on the winning side, but you have not done the political study, values clarification, or personal work of distancing yourself from oppressive forces, it's going to be very hard for you to stand in your integrity in the face of critique.

In terms of how to respond, I can speak to a few things that RadComms actually did. We put out a statement recently, and we got a lot of affirmation and support. And we also got some pushback and some critique. Reaffirmed that RadComms holds an abiding commitment to the liberation of all oppressed people. We pulled receipts and gave examples of where we had actually named these positions throughout the history of our network, that this was indeed not new. We asserted that the language and framing we used in our statement reflects what we have learned from the analysis and expertise of the impacted community, in this case, Palestinians. And that our message was informed by the attitudes, the beliefs, the opinions, and the ideas of those inside of our network, who shared resources and feedback, and also, from our own political education.

We asserted our non-negotiables. That included for us that we had a commitment to prioritizing the voices of people who were systematically excluded from establishment nonprofit spaces. And that it is our mandate as narrative practitioners on the left to contend for power, to address uncomfortable truths, and to fight for the liberation of freedom for all people. And then, finally, we actually invited people to sit with our statement and our response to them and assess if RadComms was actually the right network for them.

Deepa:

So we're close to the end and [inaudible 00:20:29] a couple minutes left. So I wanted to ask you where folks can find you. I know that you're teaching at CUNY. You have an upcoming anthology.

Shanelle:

Our website is radcommsnetwork.org. You can find lots of information there. We do have an anthology coming out. My co-editor is Marzena Zukowska, who is a Polish migrant organizer in the UK. The anthology looks at the first 20 years of the 21st century, at narrative interventions that were implemented by the left and progressive movement communications workers. It covers everything from anti-War on Terror, on COVID and HIV, to Black Lives Matter, climate, of course, gender, Me Too. It's a text that we believe that we would've really benefited from if we had it when we started doing our movement work.

Deepa:

And really excited about your anthology. I think that'll also be a text that a lot of us can learn from. So as we close it out, I wanted to just again remind folks that, at the Building Movement Project website, buildingmovement.org or at solidarityis.org, you could find general information about the solidarity principles that I mentioned, as well as the resource called How to Write a Solidarity Statement, that organizations can use to build out their process. So with that, Shanelle, thank you so much for joining us. I learned so much. Really appreciate you and your generosity of time and spirit to be here. And to our team at BMP, UyenThi, Adaku, and Jas, thank you so much for helping to make this happen. And to everyone who joined, grateful that you're here and hope that you have a restful day. Bye, Shanelle.

Shanelle:

Bye, everyone.

UyenThi:

We hope you found the conversation between Deepa and Shanelle to be useful for your individual and organizational solidarity practice. Keep an eye on www.solidarityis.org and on the BMP Instagram page at @BuildingMovementProject for resources related to the episode. And please take a look back at the episodes we've released this season, featuring organizations and people who are using public art and sites of conscience to reveal and visualize histories, subvert dominant ideologies that separate and divide people from one another, and share new narratives that help us explore connections and commonalities. See you for the next episode of Solidarity Is This, which will feature a conversation between our BMP colleague, Adaku Utah, and Cara Page, a Black queer feminist cultural memory worker and organizer. Thank you for listening, and take care of yourselves and your communities.

Related resources from BMP and SolidarityIs:

- Writing A Solidarity Statement: Considerations and Process Questions. We developed this as part of our ongoing workshops and trainings about transformative solidarity practice. In the resource, you’ll find questions to reflect on before, during, and after drafting a solidarity statement. You’ll also find examples of important moments that could catalyze a Solidarity Statement and examples of inspiring statements from different groups and networks.

- Constructing Solidarity Narratives in Challenging Times. In this resource, we share frequently asked questions and offer direction and ideas for nonprofit and movement partners to consider in moments of crisis

Resources mentioned in the episode:

- Radical Communicators Network

- Solidarity Statement Example - Blacks4Palestine

- On Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism and Dangerous Conflations via Jewish Voice for Peace